The 1918 Spanish Flu is having a moment. People don’t usually talk about the Spanish Flu unless another pandemic rears its ugly head, as Covid-19 is now. Just this week the New York Times published two articles about how New York City and Philadelphia fared during the Spanish Flu. While both cities suffered greatly it hit Philadelphia particularly hard. The doomed decision to hold a parade on Broad Street to show support for World War I had deadly consequences.

The Spanish Flu Then and Now

I’ve always had a fascination with the Spanish Flu. Philadelphia was my home for years and I’ve attended many a Mummer’s parade on Broad Street. I completely understand why that location was a petri dish for the disease’s rapid spread throughout the City of Brotherly Love. These days I live in New York City where today’s relentless headlines echo ones written 102 years before.

But my strongest connection to the Spanish Flu comes from my family. My great grandmother Ruth died in the 1918 Spanish Flu, and I look an awful lot like her. So much so that my mother gave me a gorgeous portrait of Ruth that had originally been given to her as a nod to how much she resembled her grandmother.

My great grandmother, Ruth, who died in the 1918 Spanish Flu

This family connection is why I feel so strangely at home as I self-quarantine in my New York apartment. Ruth’s portrait hangs in my living room above my couch. I feel like I have a front row seat on my personal Timetravel Pandemic Express where I quietly observe this virus sweeping the globe, and connect some dots between then and now.

Family Flu Ties

I don’t know much about Ruth. When I was little I knew her sister, known to everyone in our family as Aunt Maude. Aunt Maude was my mother’s great-aunt and I remember her as being ancient—so old and frail looking that I was afraid of her. Aunt Maude was always impeccably dressed and well-mannered. I remember suits with a pin, pearls, her white hair always on point—the embodiment of my mom’s WASP side of the family. What we know about Ruth must have come from Maude. I recently drilled my mom for any details she could remember, and here’s what she told me.

Ruth came from a family of doctors and ministers and married Willis, a medical missionary. They went to South America when the Panama Canal was being built, and served as medical missionaries during their travels. Details are hazy but they must have gone all over because their first daughter, my grandmother Betty, was born in Colombia in 1916. They made their way back to the states where Ruth had her second daughter Alicia in 1918, just as the Spanish Flu was taking hold. Ruth was the only one in the immediate family who got sick. Like most victims she died young, at either 24 or 26.

History’s Rhythm and Rhyme

The Spanish Flu’s always in the back of my mind. Years ago a friend and I went to Philly’s fabulous Mutter Museum, the ground zero of grotesque. My heart jumped when I saw they had an exhibit about the 1918 Spanish Flu (I think there’s an updated one there now). As I took in the images and explanations of coffins, masked people, and public service ads set against the backdrop of WWI, a caption jumped out that has stayed in my head ever since.

The caption put the Spanish Flu’s death toll into perspective. It said that more people died in the Spanish Flu than of all the soldiers who fought in WWI and II combined. Since then I’ve read other statistics that say the Spanish Flu is the deadliest pandemic of all time. It’s killed more people than AIDS, The Black Death, or just about anything else. Totals vary but the CDC estimates it killed about 50 million people worldwide, with about 675,000 in the United States.

All this death in less than a year, and still no one ever really talks about it. This is what blows my mind about the Spanish Flu. The caption gave a good explanation why that’s the case. All that death on top of the trauma of WWI was too much to handle, and no one could bear to talk about it. As a result the country developed a sort of collective amnesia about this slice of time.

A description of the Spanish Flu from “Pale Horse, Pale Rider”

Even though the survivors more or less decided to not talk about it and move on, you can find first-hand accounts of the Spanish Flu. Find a copy of Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider to read her fictionalized, vivid account of having the Spanish Flu. A few years ago PBS’s “American Experience” produced an excellent documentary on the 1918 flu, which includes interviews with survivors. The CDC’s website is a great source of information for all kinds of recent pandemics, Spanish Flu included.

The Spanish Flu Today

My heart is breaking for everyone affected by Covid-19. I can’t stop thinking about the mark this illness will leave on families left behind. Lately, I’ve been wondering what the last days of my great-grandmother’s life were like. I hope she didn’t suffer much but she probably did; I hope she at least died quickly, like most seemed to.

Her death must have traumatized the family. After she died her husband’s health declined. He eventually needed a wheelchair to get around and ended up killing himself at 36. Family lore said he wanted to end his suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, but who really knows. I believe Betty and Alicia lived with Maude for a while, which must have felt like charity even if it wasn’t. Betty went on to marry my grandfather Melvin, himself a doctor who served as a medic in World War II.

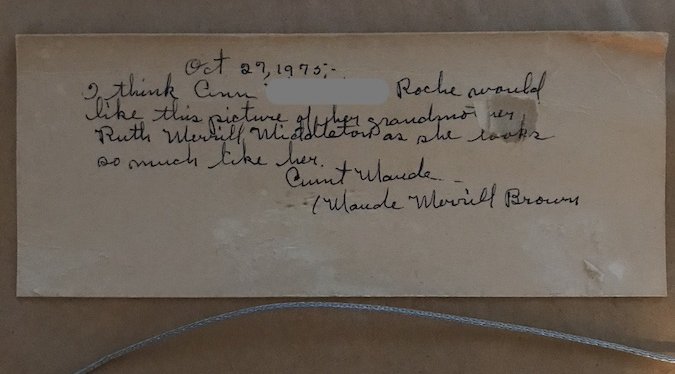

When my Great Depression mentality lifts, I’ll sign up for Ancestry.com and research my family’s past. For now the only solid connection I have to my Spanish Flu doppelganger is the inscription on the back of the portrait. It was written by Aunt Maude in her slightly shaky, formal script. On October 27, 1975, she wrote to my mother:

“I think Ann[e] Roche would like this picture of her grandmother, Ruth Merrill Middleton as she looks so much like her. Aunt Maude / Maude Merrill Brown”

The inscription my Aunt Maude wrote to my mother

Love it Em,

Thanks for reading – I’m so glad you liked it!